People's Treasure

Rao Jodha founded Jodhpur on Pachetia Hill, as in this area, there was an immense potential for harvesting and collecting rainwater and perennial water springs were visibly flowing between the rocks. The system that was discovered 500 years back, is still functional and is still serving usable water to many spaces and people.

Water into the Old City

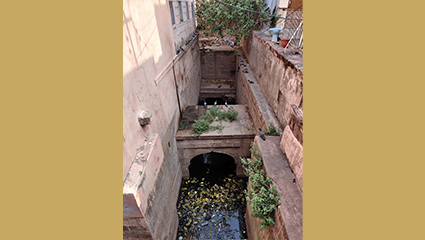

Water collected via rainwater in large catchments percolates into the ground and due to the nature of the rock, it travels through its fissures making natural pathways. Water structures in Jodhpur historic city like bawdis (stepwell), jhalaras (square stepwell), bera (well), and kunds (reservoirs) are constructed on these natural pathways. The water system in Jodhpur depends on seepage, percolation, and the water holding capacity of the rock strata. The water from hills and the higher region flows into reservoirs and further into the city enabled by the natural gradient. Jodhpur thus developed downstream where it could receive this water. This is the reason why a set of water bodies were constructed in a connected network.

Street from Padamsar to Navchokiya

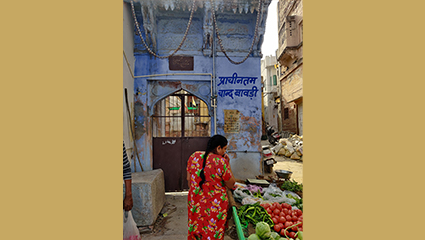

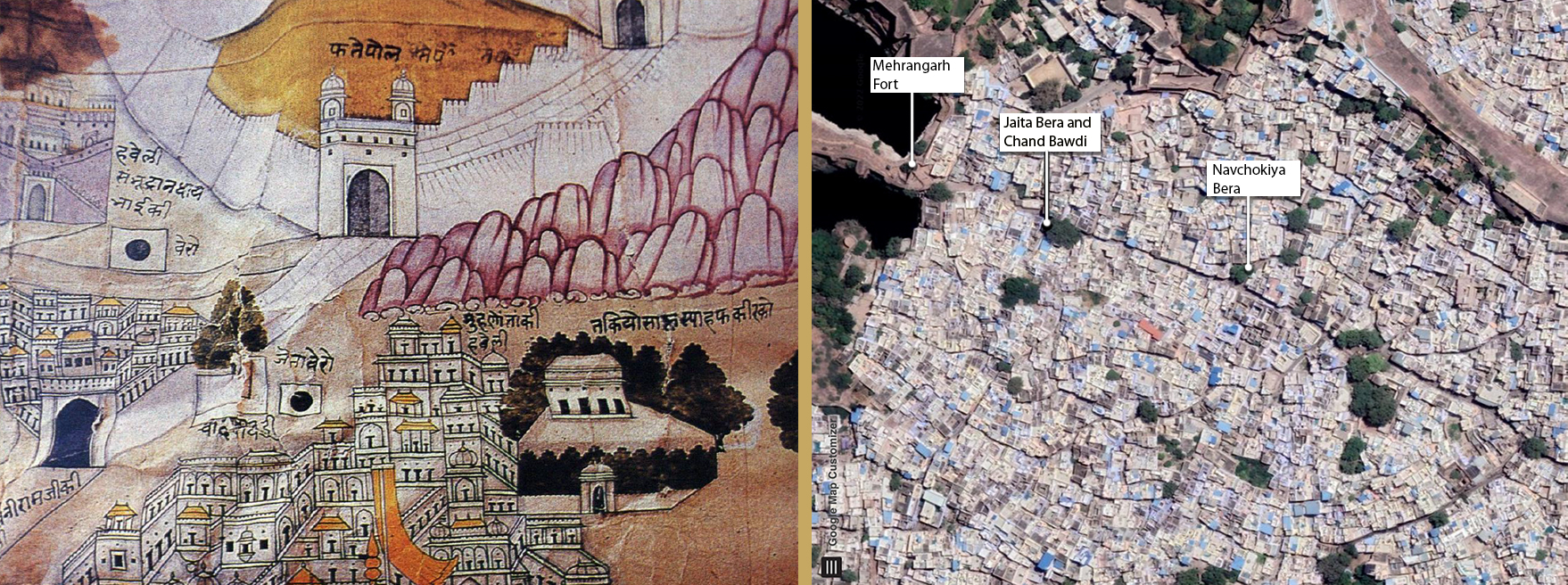

The entrance that connected the historic walled city to the Mehrangarh Fort has two lakes beside it. Ranisar was reserved for the use of the Fort and Padam Sar was open for public use. The street that connects this entrance of the Fort to the walled city is again set on a hilly terrain along the foothills of Mehrangarh Fort. Because of the presence of this hilly terrain, the dwelling has a natural gradient thus enabling the flow of water. From the perspective of the water heritage of the old city, this street can be seen as having a series of the oldest water structures either commemorated by the then ruling kings or queens or a community head.

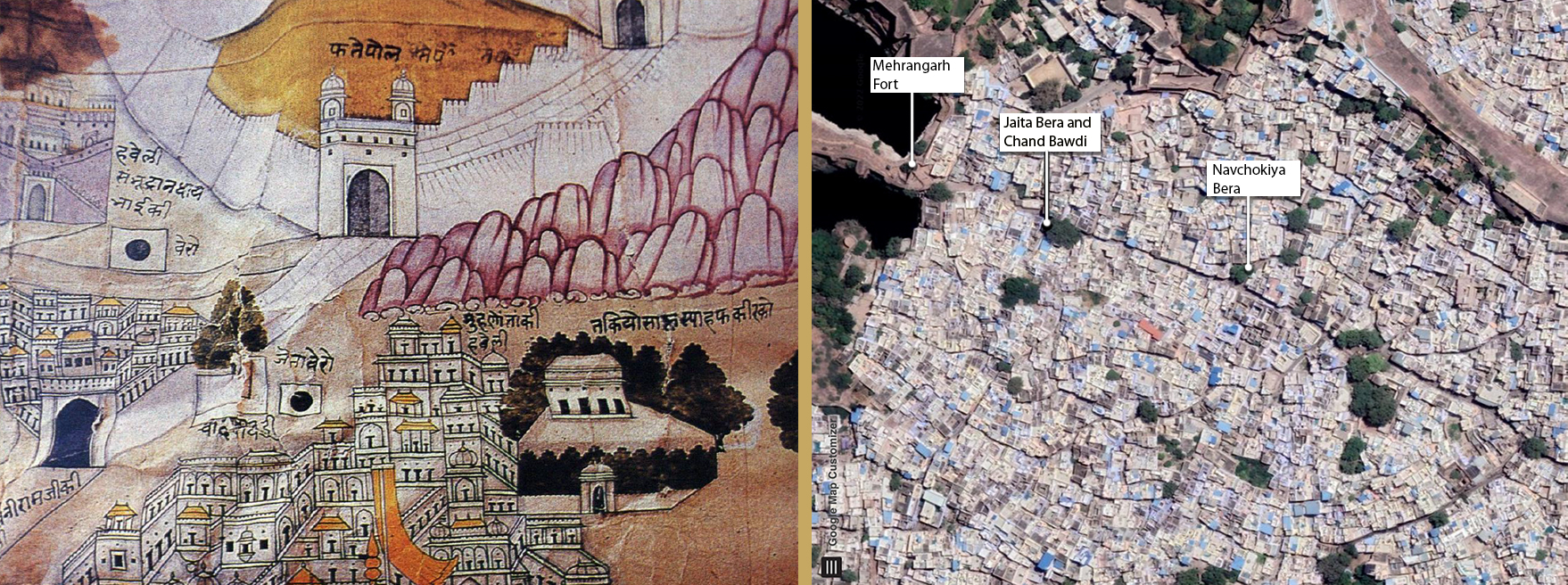

1. Jaita bera and Chand bawdi are depicted as part of the Old City adjacent to Mehrangarh Fort as seen in a traditional painting from the archives of Mehrangarh Museum Trust.

2. A screenshot from Google Earth depicting an aerial view of the street from Padamsar to Navchokiya Bera.

Padamsar Lake

Padamsar, adjoining Ranisar, is the second most prominent water body of the old city of Jodhpur. Its construction was sanctioned by different patrons at different stages, the major being Rani Utamde, wife of Padam Shah of Mewar, and Rani Devvadijee, wife of Rao Ganga. An outlet present at a lower level beneath Ranisar's overflow acts as the main source of water (cascading lake system). When Padam Sar is full, the brimming water flows from the top of the embankment and then right through the city. This system of water overflow from Ranisar into Padamsar was developed according to the engineering skills prevalent during Rao Maldeo's time and is still sustaining.

Community Wells

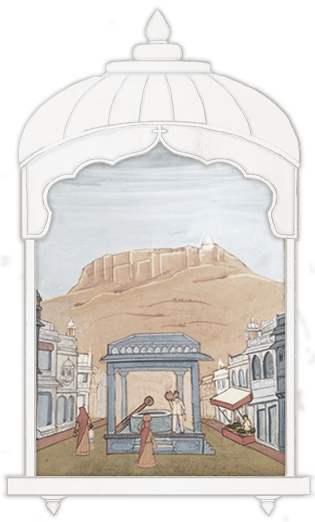

Water bodies were also commissioned by different communities. The system of water bodies ensured the presence of a network of diverse, open spaces in an otherwise dense and compact city, integrating access to water with public spaces at all scales. At these wells, which are found in every chowk (square), which catered to residents of the local community, groups of people would collect and spend time together. Even the smallest kuan/bera/well had a plinth or an otla or steps, a tree, and often a pavilion as elements that enabled the creation of social space. Spilled water was collected in troughs for animals, a manifestation of the interstitial spaces of cultural expression of a society with strong bonds to animals in everyday life. The tree is often the peepal tree (sacred fig tree) that has religious significance. The daily prayers are recited here. Bird feeders are placed here.  An artistic representation of the space and activities around Navchokia Bera. Depicting local residents using water for drinking, storing and rituals. Apart from local residents, street vendors, autorickshaw drivers, shopkeepers and passersby also consume water from the well. Illustration by Payal Gupta with inputs from Sakshi Boliya, Kavita Sachwani, Aparna Vaidik and Digvijay Singh Rathore during Jal Jharokha workshop December 2021.

An artistic representation of the space and activities around Navchokia Bera. Depicting local residents using water for drinking, storing and rituals. Apart from local residents, street vendors, autorickshaw drivers, shopkeepers and passersby also consume water from the well. Illustration by Payal Gupta with inputs from Sakshi Boliya, Kavita Sachwani, Aparna Vaidik and Digvijay Singh Rathore during Jal Jharokha workshop December 2021.

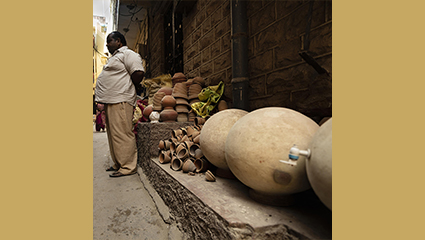

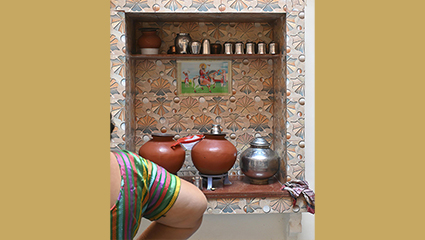

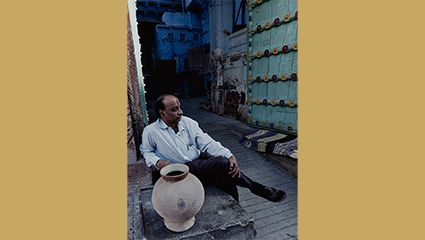

Matka: The Cycle of Life

Matka is a local word for the commonly found terracotta drinking water pots across India. The spaces where the matkas are kept, are the most religious and sacred spaces of the Rajasthani household. The place to keep a matka is called Parinda. The Parinda has quite basic niches or ledges in the wall with circular rings at the bottom to hold the pots. In a residential space, historically two Parindas were constructed, first near the entrance for passersby and the other inside the kitchen for family consumption.

The Journey of Matka is a visual story captured within the spaces of the old city of Jodhpur presenting a transition of contexts around the matka from a potter's space to a vendor's shop followed by its use, the act of destroying and then being reborn in a different context. This visual story was produced by Maya Dodd, Vijayaditya Singh Rathore, Anshul Singh during the Jal Jharokha workshop, December 2021.