Traditions of Tunes and Tones

Art and music have the power to create a different world for a moment. These temporary worlds are shaped by the unbound imagination of artists, their expressions create a specific mood, to transport us somewhere between the real and the fantastical. Jodhpur has rich traditions of such artistic practices which flourished over centuries through royal patronage and the cultural practices of common people. This story sheds light on only a few of the many examples of traditional music and miniature paintings that revered aspects of water in the artistic history of Jodhpur.

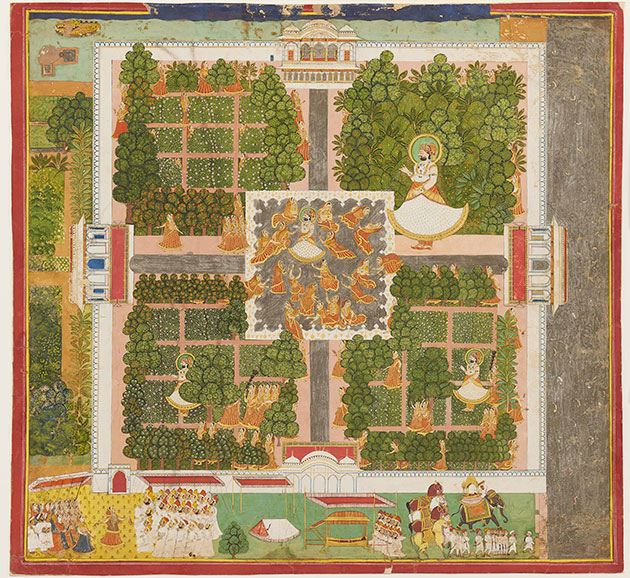

Celebrations on the festival of Kajali Teej (Badi Teej), Jodhpur

Jodhpur C. 1830-40 | Opaque watercolor and gold on paper | © Mehrangarh Museum Trust

![]() Tap to explore painting in detail

Tap to explore painting in detail

Teej refers to the monsoon festival observed particularly in the western and northern states of India. The festival celebrates the bounty of nature, arrival of clouds and rain, greenery and birds with social activity, rituals and customs. The monsoon festival of Teej is primarily dedicated to Goddess Parvati and her union with Lord Shiva. Teej refers to the third day that falls every month after the new moon (Amavasya), and the third day after the full moon night of every lunar month. Teej festival is traditionally observed by women to celebrate the month of Shravan. Here the painting shows dark, swirling monsoon clouds, the scene is set in a lush garden with marble pavilions. Maharaja Man Singh (r. 1803 - 43) is rejoicing passionately with his zenana (a private space for women). The royal party is feasting, swinging on a jhula, playing a game of dice (chaupad), and indulging playfully in hide-and-seek. Peacocks dot the landscape, and the artist Dana has depicted women in pairs, echoing the mood of the season.

"Jhir Mir Barse..."

The folk music tradition of Rajasthan is rich and diverse. Western Rajasthani folk music tradition shares its connections with bordering areas of Sindh, Kutch and Mewar. Often the songs are composed and performed by a group of people from communities like Langa or Manganiyar. The songs start with Aalap and involve singing with folk instruments including, but not limited to ravanhatha, morchang, khartaal sheets, dholak, harmonium etc. These songs, responding to the arid geography, focus on monsoons and events/festivals around monsoons, water bodies and life around them with a theme of separation.

The presented folk song is of unknown origin, here performed by Irrfan Khan (Vocal), Anish Khan (Vocal), Insaf Khan (Vocal), Rahish Khan (Vocal), Sadik Khan (dholak) and Iklas Khan (Shindhi Sarangi). This is a quintessential folk song representing the cultural geography of the region where rain is celebrated and often compared with all the pious, chaste and happy moments and events of people's lives in the desert.

In the first paragraph of this song, the earth and rain god Indra are illustrated as lovers where the earth has a chunari (piece of cloth) of clouds. In the song, the singer is assumed to be a married woman who parted with her lover and missed him during monsoon events, such as nights with lightning, thin showers, etc. The song also mentions a very important festival, Teej of Savan, associated with the divine couple of Shiva-Parvati, observed by women and dedicated to their husbands' long life. This festival falls during the monsoon season and inevitably involves swings, showers and singing.

Maharaja Man Singh and ladies of the zenana in the Garden palace at Sur Sagar

Jodhpur C. 1820 - 30 | Opaque watercolor and gold on paper | © Mehrangarh Museum Trust

![]() Tap to explore painting in detail

Tap to explore painting in detail

Jodhpur has hills surrounding Mehrangarh Fort and is a catchment area for monsoon water that flows down into small and large depressions. Its medieval inhabitants converted them into lakes from where water was drawn to hundreds of step-wells and jhalaras built in different periods in the walled city and beyond. Every neighbourhood in the old city had its own bawdi. Similarly, royal palaces were also built near the water catchment areas. As we can see in miniature paintings all the palaces had their own water bodies or jhalaras which brought life to the royal palace as these water bodies were the primary source of water during the summer season. In this painting, we can see the Sur Sagar palace and its water pond (Talab) on the right which is called the Sur Sagar Talab. The palace and pond were built by Maharaja Sur Singh in 1664. The marble Sur Sagar palace and Char Bagh pattern garden depicted by the artist in this painting are a visual delight. These water bodies not only provided water to their inhabitants but also a refuge to birds and a variety of aquatic life. Teeming with life they were a cool refuge from the heat of the desert to spend some time in

"Dal badli ro...”

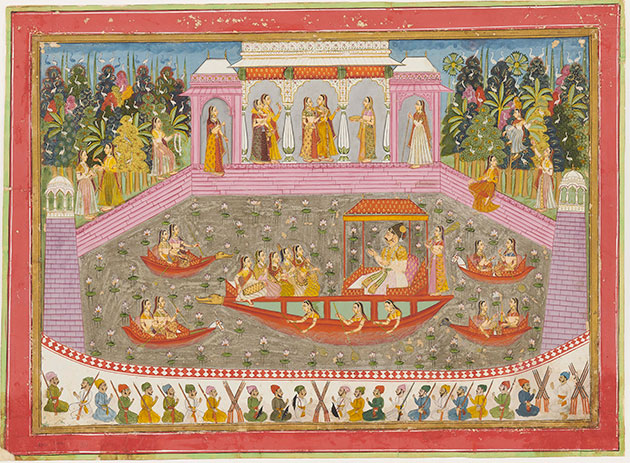

Maharaja Bakhat Singh Revels in a Pleasure boat Ride, Nagaur

Nagaur CA - 1745-48 | Attributed here to the “Nagaur Master” | © Mehrangarh Museum Trust

![]() Tap to explore painting in detail

Tap to explore painting in detail

In the late 18th century Maharaja Bakhat Singh (r. 1724-51) redeveloped Ahhichatragarh - the fort of Nagaur, setting his towers and pavilions among lush gardens, constructing huge water tanks for bathing and boating in a land of scanty rain The water system at the Fort is integrated with gardens to enhance the experience, transformation and customization to weave in with the architecture making their presence all the more pertinent to their making. The primary function of the Fort as a leisure palace and a stopover for the royal caravans between Delhi and Jodhpur with its camp-like references in architecture is enriched by the diverse open spaces. Many of the open spaces were visualized as gardens with evidence of the plantation and vegetation seen in the miniatures that adorn the palace. The sharpness and ruggedness of the stone can be imagined moderated by the soft filtering light, the hues of green and the chirping of the birds.

In 1747, an unprecedented severe famine raged throughout Rajputana and western India. As a Maratha observer wrote, “Men, it seems, cannot even get water for washing their faces.” In contrast to this heartbreaking description, the painting suggests a very different environment: a vision of relief from the oppression of a sweltering day. The lush vegetation and water tank large enough to accommodate numerous boats depict a paradise far different from the western desert region that surrounds the Fort. In the painting, four smaller boats filled with pairs of women and one large boat for the Raja and the female musicians float on the lotus-filled water. Tin alloy has been used by the artist to give the water a silvery scene.

Each boat has a distinguishing and charming prow: two are horses, two are makaras (crocodiles) and one is an elephant-the “gondoliers” of the Raja's vessel. The tank surrounded the Mahal (water palace) at one end for viewing activities, and the bastion towards the sides - all designed to protect the miniature lake.